Contents

Louise de Bettignies, the Alice Network and Léon Trulin

The word "resistant" was a Second World War term and not used during the Great War, instead the older term "spy" was applied to any person rebelling against the occupying forces in the years 1914–1918.

For the most part the Allies were looking for specific information about the German Army and this led them to recruiting agents in the occupied zones who would be in a position to gather and transmit such intelligence. Folkestone was chosen for an Allied intelligence bureau under the command of a British officer, Major Cecil Aylmer-Cameron. The Folkestone Bureau received information from the French and Belgian intelligence agencies; however it was not until March 1918, when General Foch was named supreme commander of the Allied Army, that it became solely responsible for coordinating Allied intelligence. Most of the communication between the occupied territories and the areas under Allied control took the form of messages carried by pigeon, their interception at various times during the war causing the destruction of several networks. The Folkestone Bureau supervised two spy rings outside the United Kingdom, one in Rotterdam, in the neutral Netherlands, and the other in the French town of Montreuil-sur-Mer, close to the front.

It was in Saint-Omer, until 1916 the British Army's headquarters under General French, that the intelligence service first contacted a young woman from the department of Nord: Louise de Bettignies. Since the beginning of the occupation she had been distributing letters from people in German-controlled Lille to their compatriots in free France. Louise de Bettignies was born in Saint-Amand-les-Eaux in 1880 to an aristocratic family which had fallen on hard times. After completing her studies at Valenciennes she found work as a governess to several wealthy families in various European countries. She was a modern young Frenchwoman who spoke English, German and Italian fluently and could get by in Russian, Czech and Spanish. In the first few months of the war she left Lille, her home until the German Army took over the town, and came to Saint-Omer as a refugee where she helped care for the wounded. France's intelligence agency, the Deuxième Bureau, was the first to approach her but she eventually decided to join the British Intelligence Service and left for England where she underwent intensive training in using codes, drawing plans, gathering information and sending messages. She also adopted the pseudonym Alice Dubois.

Louise de Bettignies was subsequently smuggled into Belgium where she was given a cover job in a Dutch cereal company in the town of Flushing. Her mission was to identify troop movements in the region of Lille, the German Army's principal logistics hub on that part of the Western Front. By the spring of 1915 the "Alice Network" involved eighty men and women of all social classes. They watched trains, identified the positions of gun batteries, munitions depots and the dwellings of officers, and helped evacuate Allied soldiers to the Netherlands. The network was aided by a Belgian national called De Geyter, the owner of a chemical factory in Mouscron, who forged their documents. Couriers were used to convey the gathered information as quickly as possible to the Netherlands. The eighty-strong personnel of the Alice Network were based in and around the towns of Lille, Roubaix and Tourcoing. Most of them worked for the railways and the postal service, but candidates could be people who travelled for a living or were used to keeping secrets, such as doctors and priests. In the spring of 1915 she enlisted the help of Marie-Léonie Vanhoutte, code-named "Charlotte Lameron", who by the summer had helped her expand the network's activity to the region around the towns of Cambrai, Valenciennes and Saint-Quentin.

From the outset of hostilities the German Army meted out brutal punishments to anyone involved in intelligence activities and by the end of the war, in the department of Nord alone, twenty-one people had been executed and many more had been given prison terms and sentenced to forced labour.

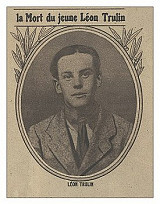

One of the most celebrated victims of the occupier's wrath was a young student by the name of Léon Trulin who had set up a small intelligence network called Léon 143 to pass information to the Alice Network. He was executed on 8 November 1915 in front of Lille's citadel, at the age of eighteen. Born in the Belgian town of Ath on 2 June 1899, Léon Trulin moved to La Madeleine-lez-Lille with his family in 1902. In the first weeks of the Great War, just after the German invasion of France, Trulin escaped to England where he tried to enlist in the Belgian Army but was refused because of his age. He then approached the British and they suggested he return to the occupied territories to set up an intelligence organization, which he did. Trulin developed the organization over the first few months of 1915, with the help of a group of young men––Raymond Derain (18), Marcel Gotti (15), André Herman (18), Marcel Lemaire (17) and Lucien Deswaf (18)–– and carried the documents himself to the Netherlands. It was on one such run that he was arrested, in the night of 3 October 1915 near Antwerp, his wallet containing several reports, photographs and plans relating to German military installations. He was sentenced to death for spying in September 1919. Léon Trulin was posthumously awarded the British War Medal and on 30 January 1920 he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire.

Crossing the Belgian-Dutch border every week to send her reports to the British, Louise de Bettignies eventually came to the attention of the German counter-intelligence service which successfully trapped her on 20 October 1915 in Froyennes, near Tournai. Held at Saint-Gilles Prison in Brussels, Bettignies was sentenced to death on 19 March 1916; however at the time of her sentencing an international campaign was in full swing to protest against the execution, also in Brussels, of the British nurse Edith Cavell and the Belgian resistant Gabrielle Petit. Bending to the pressure the governor of Belgium, General von Bissing, reduced her sentence to forced labour for life and on 21 April 1916 she was sent to Sieburg Prison. But her fame and reputation were rapidly growing in France and Great Britain and, on the eve of her transfer to Sieburg, General Joffre commended her actions in an official dispatch of the French Army.

She was held in dreadful conditions, which worsened after she was discovered inciting her co-detainees to stop working for their captors, and she soon fell ill with pleurisy. She was subsequently transferred to Sainte-Marie Hospital in Cologne where she died on 27 September 1918 for want of proper medical care. Her body was transported to Lille in March 1920 and given a state funeral. Her final burial place was in her native town of Saint-Amand-les-Eaux. The wooden cross used by the Germans to mark her first grave in Cologne has been on display in the basilica of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette since 1994.

Various monuments in Lille commemorate the "resistants" of the Great War:

- statue of Louise de Bettignies, boulevard Carnot,

- statue of Léon Trulin, on the street which bears his name, close to Lille Opera,

- monument to the executed leaders of the Lille Resistance, at the entrance to the esplanade of the citadel.

Yves LE MANER,

Director of La Coupole,

History and Remembrance Centre of Northern France

The Lille Resistance : le Comité Jacquet

Eugène Jacquet––wine wholesaler, general secretary of the Nord branch of the Human Rights League, socialist, Freemason and pacifist––joined the movement for political unity, the Union Sacrée, in 1914. He had lived in the USA and the UK and so was a fluent English speaker. With his friends Georges Maertens, Ernest Deconinck and the Belgian Sylvère Vehulst, and with the support of Prefect Félix Trépont, he set up a resistance group to collect intelligence and smuggle people out of the occupied territories.

Among its members were the Plouvier brothers, textile industrialists who provided financial backing, professional fraudsters Gaston Lécuyer, Léon Vestens and Hyppolyte Cloots who organized transport and Jean Vandenbosch who handled intelligence.

The downfall of the Jacquet Line (Comité Jacquet) was brought about by the Mapplebeck Affair. In March 1915, after dropping its payload on the Esquermes area of Lille, a British bomber was forced to land in Wattignies although the pilot, Lieutenant Gilbert Mapplebeck, managed to avoid capture. He was taken in by the Jacquet Line who organized his escape back to Great Britain and he soon returned to active service. During his next flight over Lille, Mapplebeck dropped a letter which mocked General Heinrich, the military governor of Lille. Betrayed by a man called Richard (who was later sentenced to deportation, in 1919) the members of the Resistance were arrested and the Germans discovered the British pilot's diary in the arm of a chair. In all more than 200 people were arrested. Eugène Jacquet was sentenced to death by Lille military court on 21 September 1915, as were his accomplices Verhulst, Maertens and Deconinck. They were executed the next day, at dawn. The other members of the Lille Resistance were given prison sentences and sent to concentration camps.

The underground press

By October 1914 Allied broadcasts from the Eiffel Tower and Poldhu wireless station in Cornwall were being intercepted and passed on orally by Jules Pinte, priest and professor of chemistry at the Technical Institute of Roubaix, and Firmin Dubar, administrator of the same establishment. From 1 January 1915, the broadcasts were being transcribed and printed at a chemist's shop using a stencil duplicator to produce several dozen copies. Initially entitled Le Journal des occupés... inoccupés (Newspaper of the Occupied... Unoccupied), the paper became La Patience (Patience) on 22 January 1915 under the guidance of its director, editor, printer and distributor, chemist Joseph Willot. Starting out as a weekly publication, the thirty-page paper was soon appearing twice a week in a small format. On 1 March 1916 it once again changed its name, this time to L'Oiseau de France (Bird of France), and was being printed in one thousand copies every edition; however on 21 October 1916 Father Pinte was caught by the Germans and, in an effort to exculpate him, Willot published La Voix de la Patrie (The Voice of the Nation) but by 19 December 1916 he himself had been arrested along with his wife, Firmin Dubar and their collaborators. Mrs Willot died in detention while the others were sentenced to ten years in prison on 17 April 1917 and sent to Rheinbach in Germany. Freed after the Armistice, the underground journalists of Roubaix returned to France exhausted. Joseph Willot died on 1 April 1919 as a result of his ordeal.

Claudine WALLART,

Head Curator of Heritage

at the Archives Départementales du Nord (Nord Records Office)